Layers of the Aorta

The Wall of the Aorta

The aorta is not just a large pipe for blood. Its wall is a carefully built structure made of different layers, each with a special role. A healthy aortic wall combines strength, elasticity, and protection, so it can handle the powerful beat of the heart thousands of times a day.

When one of these layers becomes weak or damaged, problems can develop. Many serious conditions such as acute aortic syndromes, aneurysms, or genetic diseases like Marfan syndrome begin with changes in the wall. That’s why understanding the wall’s structure helps explain why certain diseases happen and why they can be so dangerous.

The Inner Layer (Intima)

The intima is the innermost layer of the aorta. It is made of smooth, delicate cells that line the inside of the vessel, creating an almost friction-free surface for blood to flow. This layer acts as a barrier between the rushing blood and the deeper wall layers.

But the intima is also vulnerable: small injuries or disease processes like atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) often start here. In conditions such as an aortic dissection, the very first tear usually occurs in the intima, allowing blood to burrow between it and the next layer.

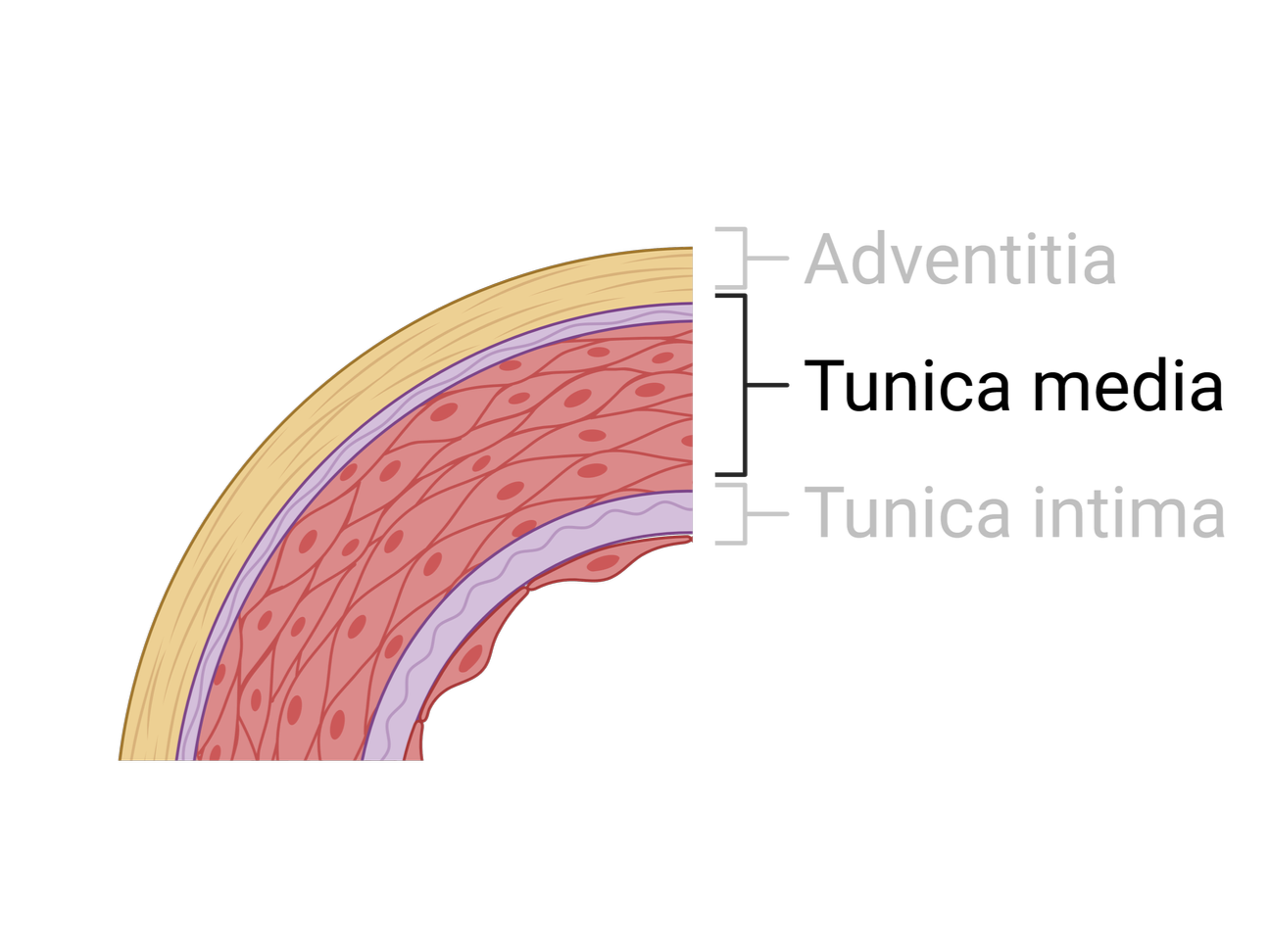

The Middle Layer (Media)

The media is the thick, elastic middle layer. Think of it as the aorta’s shock absorber. Every time the heart pumps, the media expands to take the force, then springs back to help push the blood onward. This stretch-and-recoil ability helps smooth the pulse and reduces pressure on the heart.

Because it carries most of the mechanical load, the media is often the focus of disease. Inherited conditions like Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome weaken the structure of the media, making the aorta more prone to enlargement (aneurysm) or tearing. Age and high blood pressure can also wear it down over time.

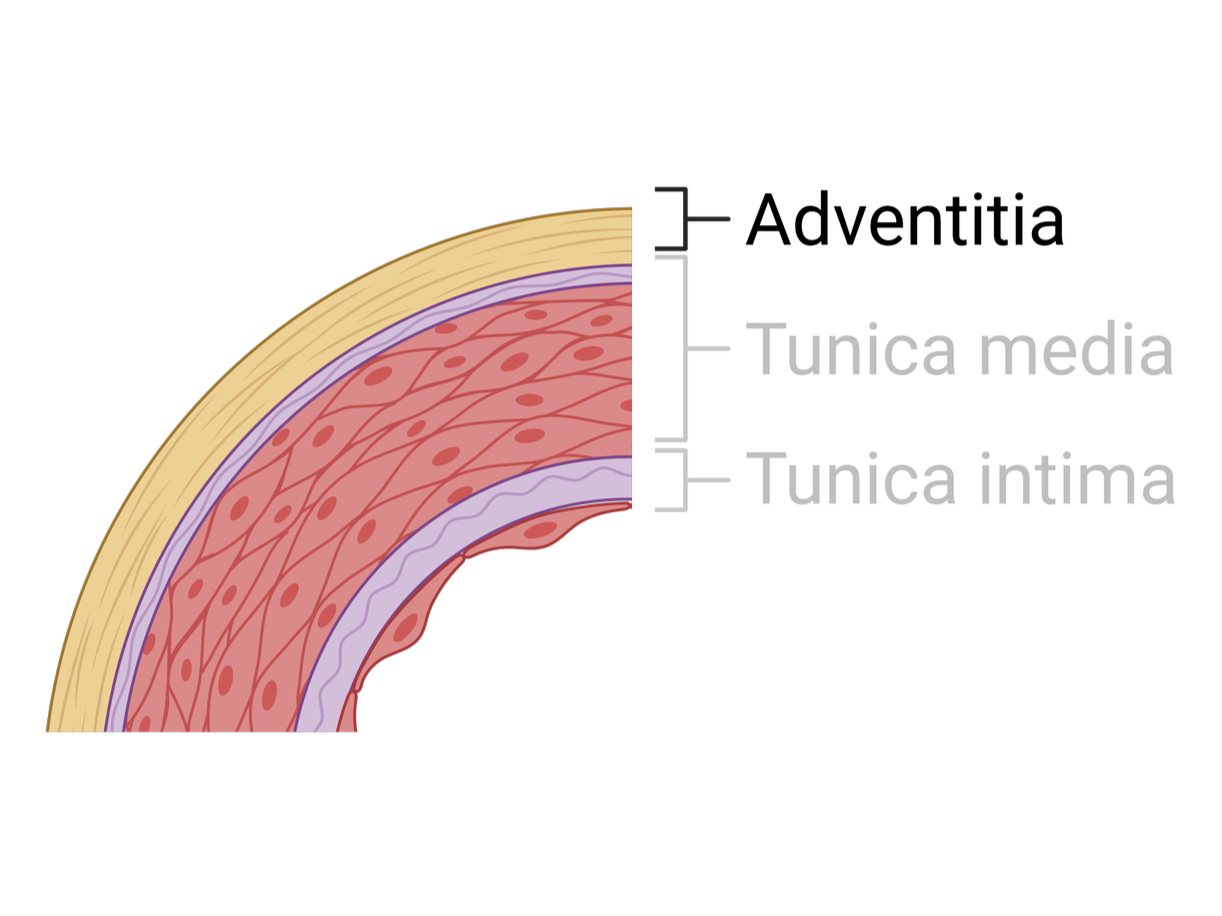

The Outer Layer (Adventitia)

The adventitia is the tough outer coat of the aorta. It is made of strong connective tissue and tiny blood vessels that nourish the wall itself. The adventitia protects the aorta from overstretching and keeps it anchored in the chest and abdomen.

While it seems less “active” than the other layers, the adventitia is crucial for overall stability. If this layer breaks down when the aorta is under pressure, a rupture can occur, one of the most dangerous complications in all of medicine.

When the Wall Gets Sick

Problems with the aortic wall can lead to a wide range of diseases:

Acute aortic syndromes: sudden, life-threatening events like dissections or intramural hematomas often begin with damage to the intima or media.

Aneurysms: long-term weakness in the media may cause the aorta to enlarge like a balloon.

Genetic conditions: disorders such as Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome make the wall more fragile and increase the risk of dangerous complications.

Atherosclerosis: buildup of fatty plaques in the intima can weaken the wall and lead to penetrating ulcers.

Each of these conditions is explained in detail in other chapters of this website. Understanding the wall of the aorta provides the foundation to see how these problems develop, and why protecting the wall is so important for protecting life.