Heredetary Aortic Disease

Overview

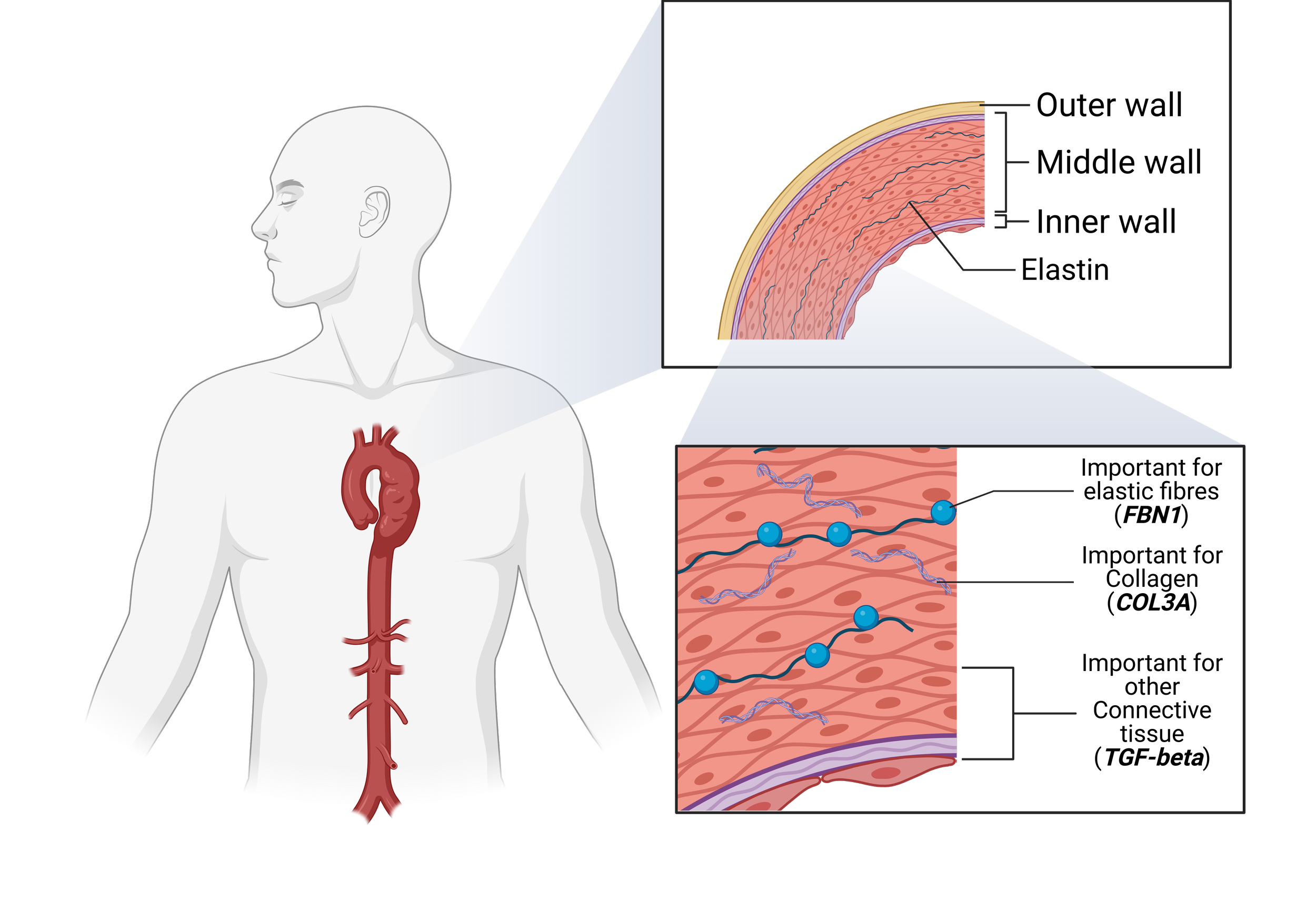

Hereditary aortic syndromes are a group of genetic disorders that weaken the structural integrity of the aortic wall, predisposing affected individuals to aneurysm formation, dissection, or rupture. These conditions are inherited and often caused by mutations in genes responsible for the production or regulation of connective tissue proteins that give the aorta its strength and elasticity. Because the aorta is the main vessel carrying blood from the heart to the body, even subtle structural defects can lead to catastrophic vascular events if left untreated.

The most common hereditary aortic syndromes include:

Marfan syndrome: caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, resulting in abnormal connective tissue throughout the body and progressive dilation of the aortic root and ascending aorta.

Loeys–Dietz syndrome: associated with mutations in genes of the TGF‑β signaling pathway (TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD2, SMAD3, and others), leading to highly aggressive aneurysm formation throughout the aorta and its branches.

Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (vEDS): due to mutations in COL3A1, producing defects in type III collagen that cause arterial fragility, spontaneous dissections, and ruptures at relatively small diameters.

Familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection (FTAAD): an inherited condition linked to mutations in genes such as ACTA2, MYH11, MYLK, and PRKG1, in which aortic disease appears across generations without other syndromic features.

Symptoms

Symptoms may remain minimal or absent until serious complications occur. However, certain clinical clues can suggest an underlying hereditary aortic syndrome.

General signs:

Chest, back, or abdominal pain, often sudden and severe when dissection develops.

Family history of early aneurysm, dissection, or sudden cardiac death.

Syndrome‑specific features:

Marfan syndrome: tall stature, long limbs, lens dislocation, scoliosis, chest wall deformities.

Loeys–Dietz syndrome: widely spaced eyes, cleft palate, clubfoot, arterial tortuosity.

Vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: thin translucent skin, easy bruising, hypermobility of small joints, arterial rupture.

Diagnosis

Early recognition is crucial to prevent fatal complications. Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical evaluation, family history, genetic analysis, and imaging studies.

Genetic testing: identifies mutations responsible for the syndrome and enables cascade screening of family members.

Echocardiography: first‑line test to measure the aortic root and ascending aorta.

CT or MR angiography: provides comprehensive imaging of the entire aorta and its branches.

Clinical criteria: physical findings help diagnose specific syndromes such as Marfan or Loeys–Dietz.

Complications

If not managed timely, hereditary aortic syndromes may lead to life‑threatening outcomes such as:

Progressive aortic aneurysm formation

Aortic dissection, often presenting as sudden, tearing chest or back pain

Aortic rupture with massive internal bleeding

Aortic valve regurgitation due to root dilation

Involvement of other arteries, including cerebral, abdominal, or peripheral vessels

Treatment

Therapy focuses on preventing aortic enlargement, minimizing hemodynamic stress, and avoiding dissection or rupture.

Lifestyle modification: Avoid strenuous or contact sports, maintain strict blood pressure control, and stop smoking.

Medical management: Beta‑blockers or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are often used to reduce aortic wall stress and slow dilation.

Monitoring: Lifelong imaging surveillance by echocardiography, CT, or MRI to track aortic size and growth.

Genetic counseling: Essential for affected patients and family members to inform risk and guide screening.

Surgical treatment: Indicated when the aortic root or ascending aorta reaches defined size thresholds or shows rapid growth. In advanced disease, open aortic root surgery remains the definitive treatment.